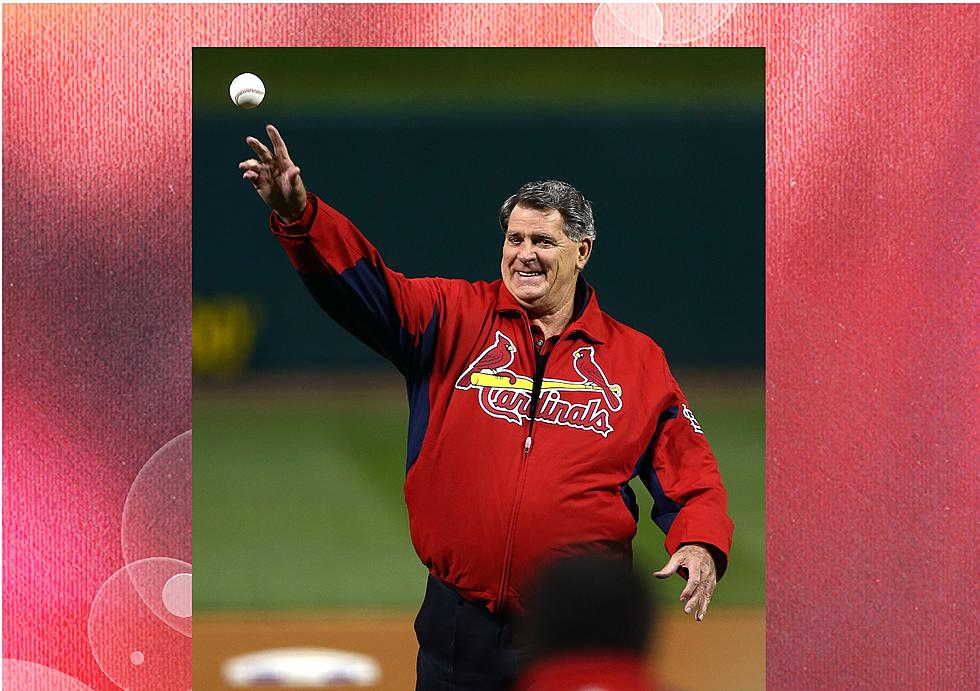

Stan “The Man” Musial Passes Away at 92

The primary baseball icon of the Midwest -- the soft-smiling, sweet-swinging, deferential and genial man known as "The Man" -- has passed. Stan Musial, known for his pretzel stance, prodigious production, princely personality and Hall of Fame harmonica, died on Saturday (Jan. 19), surrounded by family at his home in Ladue, Mo., not far from St. Louis, where he made his mark as a batsman par excellence in the 1940s and '50s. Arguably the greatest left-handed hitter in National League history was 92.

His stylish, spring-loaded stance and oft-repeated swing -- for years, Musial swung an invisible bat as his greeting or bow -- and the remarkable numbers they produced for the St. Louis Cardinals placed The Man among the most distinctive and elite players in baseball's long history. He won three National League Most Valuable Player Awards, three World Series, seven batting championships, the hearts of millions and the enduring nickname that was as unembellished as he was.

Musial was marked by conspicuous modesty, unfailing propriety and utter lack of flamboyance, as sportscaster Bob Costas observed in a passage from ESPN's SportsCentury series: "He didn't hit a homer in his last at-bat; he hit a single. He didn't hit in 56 straight games. He married his high school sweetheart and stayed married to her, never married a Marilyn Monroe. He didn't play with the sheer joy and style that goes alongside Willie Mays' name. ... All Musial represents is more than two decades of sustained excellence and complete decency as a human being."

Consistent with that description was the presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Musial by President Obama at the White House on Feb. 15, 2011. An American civilian can receive no greater honor.

MLB Commissioner Allan H. "Bud" Selig offered his condolences in a statement released shortly after Musial's death.

"Major League Baseball has lost one of its true legends in Stan Musial, a Hall of Famer in every sense and a man who led a great American life. He was the heart and soul of the historic St. Louis Cardinals franchise for generations, and he served his country during World War II. A recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011, Stan's life embodies baseball's unparalleled history and why this game is the national pastime.

"As remarkable as 'Stan the Man' was on the field, he was a true gentleman in life. All of Major League Baseball mourns his passing, and we extend our deepest condolences to his family, friends, admirers and all the fans of the Cardinals."

Musial, father of three daughters and a son, was unpretentious, untroubled, friendly and folksy. The harmonica he played at Hall of Fame weekends and other public gatherings fit his image and humanized him for the masses who saw him as a Louisville Slugger deity. It was as though he copyrighted the greeting, "Whaddya say? Whaddya say? Whaddya say?" The words always came with a gentle smile.

Hall of Fame chairman Jane Forbes Clark shared her thoughts on Musial's passing: "Stan was a favorite in Cooperstown, from his harmonica rendition of 'Take Me Out to the Ballgame' during Hall of Fame Induction Ceremonies, to the reverence he commanded among other Hall of Fame members and all fans of the game. More than just a baseball hero, Stan was an American icon and we will very much miss him in Cooperstown."

Former Cardinals manager Tony La Russa once called George Kissel, the late Cardinals coach of fundamentals and resident baseball genius, "The nicest person in the world." And after a moment's pause, he added, "Musial is only percentage points behind."

Before the game expanded in the early '60s, the Midwest knew four teams, two in Chicago and two in St. Louis. And the Cardinals had the highest profile in the region, the residue of the Gashouse Gang, the Dean Brothers and Pepper Martin. They were the league powerhouse from 1942-46, fueled primarily by Man-power.

Musial was to the Cardinals what Joe DiMaggio was to the Yankees and Ted Williams was to the Red Sox. Folks who kept their radios tuned to KMOX in those summers would argue whether Joe D. and Teddy Ballgame were to their respective teams what Musial was to his. The Man was their gold standard, although routinely attired in red.

If doubts about Musial existed after his first five full seasons -- during which he won two batting titles and two MVP Awards -- they were dispelled after his magnificent 1948 season. He led the National League in runs (135), hits (230), doubles (46), triples (18), RBIs (131), batting average (.376), slugging percentage (.702), on-base percentage (.450) and total bases (429) and finished second, by one to Ralph Kiner, with a career-high 39 home runs. A 40th was lost to a rainout.

His total bases are the second most in history. Musial won his third MVP Award in 1948, though somehow he wasn't a unanimous choice. He even had a sacrifice bunt. Indeed, this remarkably accomplished batsman sacrificed 35 times in his career, more than DiMaggio and Williams combined. Or is the more remarkable figure a zero? Musial was ejected from none of the 3,026 games he played.

Perhaps because of the predominance of East Coast media, Musial's prowess was somewhat obscured, first by DiMaggio and Williams in the '40s and by Mickey Mantle, Mays and Henry Aaron in the '50s and into the '60s. Moreover, when the team of the 20th century was elected in a vote of fans in 1999, Musial was one of five preposterous omissions -- Lefty Grove, Christy Mathewson, Warren Spahn and Honus Wagner were the others -- who were added to the team by a vote of a special committee.

Having been assigned to first base in 35 percent of the games he started in his 22 seasons, Musial placed 11th among outfielders in the balloting. He was the first player to appear in more than 1,000 games at each of two positions.

But when he was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1969, The Man was named on 93.2 percent of the ballots cast, a percentage comparable to or greater than four of the other five -- Mantle (88.2), DiMaggio (88.8), Williams (93.4) and Mays (94.7). Hank Aaron received 97.8 percent of the vote when he was elected in 1982. And Musial was elected in his first year of eligibility, at a time when first-year election still was recognized as extra-special.

Don't ever try to persuade a Cardinals disciple that Musial was something less than any other player. Even now, nearly a half-century after his retirement, he is held in the highest regard in St. Louis and its baseball suburbs. The Cardinals have numerous Hall of Famers on their all-time roster. Among the living are Bob Gibson, Ozzie Smith, Lou Brock, Red Schoendienst and Bruce Sutter. When they appeared together, Musial was routinely introduced last, an honor afforded DiMaggio with the Yankees and Williams with the Red Sox when they were alive. Mays, with the Giants, and Aaron, with the Braves, still are recognized last.

Mays shared his thoughts after learning of Musial's death: "It is a very sad day for me. I knew Stan very well. He used to take care of me at All-Star Games, 24 of them. He was a true gentleman who understood the race thing and did all he could. Again, a true gentleman on and off the field -- I never heard anybody say a bad word about him, ever."

Musial's rank in several career offensive categories is significantly closer to first despite missing the entire 1945 season to serve in the United States Navy. When he retired after the 1963 season, he shared or held 17 big league records and 29 National League records. He currently ranks in the top 10 in five career categories -- second in total bases (6,134), third in doubles (725), fourth in hits (3,630), sixth in RBIs (1,951) and ninth in runs (1,949). His .331 career batting average stands 30th. He received MVP votes in 18 seasons, finishing as the runner-up four times after winning his third award in 1948. He was second in the balloting in 1957, when at age 36, he won the NL batting title for the final time. He won his seventh title -- only Ty Cobb (11), Honus Wagner and Tony Gwynn (eight each) won more -- 14 years after his first.

And he may well rank first in autographs given. Every year was a signature for The Man. He declined a request for his Stan Musial as often as he was ejected.

Hence, the Man-made legend and the words at the base of the statue of Musial outside the third Busch Stadium in St. Louis: "Here stands baseball's perfect warrior. Here stands baseball's perfect knight." What better place for folks to meet?

Even Albert Pujols, who might have eclipsed some of Musial's career totals with the Cardinals had he remained in shadow of the Arch, deferred to The Man. After "El Hombre" evolved as his nickname, Pujols requested that he not be so identified, even though his nickname was a complimentary nod to Musial. "I don't want to be called that," Pujols said in February 2010. "There is one man who gets that respect, and that's Stan Musial. He's The Man. He's The Man in St. Louis. And I know 'El Hombre' means 'The Man' in Spanish. But Stan is The Man. You can call me whatever else you want, but just don't call me 'El Hombre.'"

Pujols had this to say on Twitter:

"My prayers are with the Musial family tonight. I will cherish my friendship with Stan for a long as I live. Rest in Peace."

The oddity of Musial's nickname is that it came from outside the Midwest, from Brooklyn, home of Dem Bums, of all places. Fans at Ebbets Field chanted "Here comes the man," each time Musial batted in a game on June 23, 1946. A column in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the following day noted the development, referred to Musial as The Man, and the nickname stuck. Musial had a more conversational nickname, Stash -- pronounced Stahsh. His father, a Polish immigrant, called him Stashu. His given name was Stanislaw Franciszek Musial.

Stanley Frank Musial, as he became known, was born in 1920 in Donora, Pa., the same town that was the birthplace of another left-handed slugger, Ken Griffey Jr., 49 years later to the date, Nov. 21. Musial was a pitcher who could hit and enough of a basketball player that the University of Pittsburgh offered him a scholarship. He chose baseball.

A shoulder injury in the summer of 1940 ended his pitching career and gave rise to a one that prompted Dodgers broadcast genius Vin Scully to say, "How good was Stan Musial? Good enough to take your breath away."

"He could have hit .300 with a fountain pen," Joe Garagiola, Musial's Cardinals teammate for five years and later a baseball announcer, said.

Warren Spahn, the most successful left-handed pitcher in Major League history, whose career ran concurrently with Musial's from 1942-63, had this to say about The Man: "Once Musial timed your fastball, your infielders were in jeopardy." So, too, were folks in the stands. Musial hit 12 home runs and batted .358 in 240 career at-bats against Spahn. The only player with more home runs against Spahn -- Mays with 18 -- batted right-handed.

And then there was Carl Erskine, the self-effacing former Dodgers pitcher who fully grasped the basis for Musial's nickname. Though The Man batted .327 in 110 at-bats against him, Erskine said, "I've had pretty good success with Stan by throwing him my best pitch ... and then backing up third."

Story is courtesy of Marty Noble, a reporter for MLB.com.

More From AM 1050 KSIS